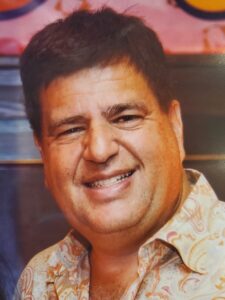

Archibald Honigman never stopped making friends, even when he was a patient with COVID-19 in St. Boniface Hospital’s Intensive Care Unit (ICU).

“When Arch was placed in the ICU last fall, he recognized the name of the first doctor who saw him. He had read about him in the newspaper, and then got to know him,” recalled Joanna Biondi, Honigman’s partner of 11 years. (They were married in 2017.) “He made friends with the nurses. All week long, a day didn’t go by that he did not have a nurse with whom he had some connection.”

As a patient, Honigman casually peppered his caregivers in the ICU with questions about their lives, trying to get to know each one of them. He would remember them on their next shifts.

Both being cancer survivors, he and Biondi were always careful in the COVID-19 pandemic. Honigman also had the precondition of Type 2 diabetes. Despite being fully vaccinated and following public health guidelines, Honigman died at the Hospital in September 2021. The cause was complications from a breakthrough case of COVID-19 caused by the highly contagious Delta variant . He was 61.

In life, Honigman looked out for others in his community. He co-founded a successful property development and management company with many staff and contractors employed in Winnipeg. His passion was buying heritage and distressed buildings for renovation.

“Somebody’s house had burned down. Arch heard about it, and he told the family, ‘You can stay in one of my apartment blocks for free until you find a place to live. Don’t worry about it.’ If he could make someone’s life happier and better, he was more than happy to step up and do it.”

Honigman was proud of his Jewish heritage. He was a caring and inquisitive person, said Biondi. “It is one thing to look after your own family, but another to take care of others’ families. Arch always took responsibility and cared about his employees and close circle of friends.”

Now, she is “eternally grateful” that he experienced the same kind of compassion and care as a patient in St. Boniface Hospital’s ICU.

Low oxygen level led to hospitalization

On September 18, four days after Honigman tested positive for COVID-19, the couple were at their home. His symptoms had developed about a week earlier, and he was still not feeling better. “Arch took a shower, and when he came out of the bathroom, I thought he hadn’t dried his hair. Then I realized, no, he was sweating,” she said.

Struck by a strange “sixth sense” feeling and concerned for her husband’s well-being, she called her brother-in-law, a physician, for help. “He came over and measured Arch’s oxygen saturation level. Seeing it was in the (dangerously low) 76% range, we immediately called 911,” she remembered.

“Arch never thought it was going to happen to him.”

Honigman was reluctant to leave and asked the paramedics if he could rest at home. Biondi thinks he feared going to the Hospital. “He was still standing on his feet. Finally, my brother-in-law had to say to them, ‘Listen, these are his numbers; you’re going to have to take him,’” she said. “Someone who had those numbers should not have been able to speak, let alone stand and walk around, as he was. Arch never thought it was going to happen to him.” The paramedics put him in a wheelchair and moved him to the waiting ambulance.

“My husband didn’t leave our home thinking he would never walk back up the steps again. Neither did I.”

Honigman arrived at the Hospital’s Emergency Department at 7 p.m. that night. Although at first stabilized and even showing some improvement, his breathing had deteriorated by 2 a.m. the next morning to the point that he had to be admitted to the ICU and put on Optiflow nasal high flow oxygen therapy.

Visiting Honigman in the ICU was not allowed due to strict pandemic restrictions that were in place. St. Boniface Hospital chaplains and nurses would regularly arrange Zoom calls between Honigman, his wife, and their family, in which his caregivers would also occasionally join. “We were so grateful for the Zoom calls. They were a lifeline,” she said. “We would all jump in, and the chaplain would tell us how he was doing and what the doctors and nurses were saying.”

“We had some great conversations on Zoom. He was often sitting up and looked great at the time. It was nice to see the environment he was in. The nurses loved Arch, and he truly adored them. It takes a special person to be a health-care provider. I don’t know how they did their jobs while catering to my husband…because trust me, they were truly catering to him. He always found a way to get what he wanted; it was hard to say no to Arch! So, I give them a lot of credit,” she said.

Honigman was also permitted the use of his mobile phone, which he used to call Biondi and his friends during his time in the ICU. The nurses made sure it stayed charged and ready for him. “Knowing we were only a call away gave Arch comfort,” she said.

Intubation needed after five nights in care

Dr. Kendiss Olafson, his critical care physician in the ICU, became concerned that Honigman’s breathing was getting worse. She decided he would need to be intubated and put on a ventilator. The hope was that his condition would improve and stabilize after another four or five days.

“Dr. Olafson was a blessing,” said Biondi. “She was a wonderful doctor, with excellent communication skills. She not only shared everything and kept you up to date, but she would also explain things in layperson’s terms, making sure I understood.”

With his intubation scheduled for the afternoon, nurses quickly arranged a Zoom call after 11 a.m. with Biondi and their family members to give them a chance to talk with him for more than a half-hour.

“We had our last Zoom call with Arch,” she said. “It wasn’t supposed to be the last one.”

“He still looked well. The nurses were with him, but that sick feeling went on my shoulder. I thought, ‘They’re going to intubate him, and I had better say some things,’” she said. “I told him how much I loved him, and that I was so happy we had met, and that I was so proud we were husband and wife.”

“We didn’t think we were going to lose him. I kept saying, ‘I can’t wait for you to come home,’ and I will never forget this – Arch asked if he was going to be home in time for Halloween, which he loved.”

“He kept saying how kind everyone in the Hospital was to him. We knew we were going to have to sign off, so they could prep him. I said my last few words to him, and I heard Dr. Olafson say, ‘Arch, it should only be for a few days.’ He asked if (intubation) was going to hurt. She leaned over and took his hand. I just wanted to hug him and hold his hand so badly at that moment, and to me, that was my hand.”

“She calmed him, and I thought, ‘How do you do that as a doctor?’ You have intelligence, knowledge, persistence, the dedication. And then on top of that, you have this big, caring heart that you are giving not only to your family but giving it to people you hardly know. It blew me away.”

For unknown reasons, Honigman’s condition declined sharply just hours after he was put on the ventilator. He went into cardiac arrest several times later that afternoon and evening. After the first time, Biondi and her sister were invited to spend time with him in person.

“Dr. Olafson greeted us at the door that afternoon, and I told her, ‘I am so grateful that you are Arch’s doctor. You have no idea. I saw you holding his hand a few hours ago, and there are no words to express how much I appreciated you doing that.’”

“And she said, ‘Joanna, it’s not just me. It’s a whole team of us.’ And when we walked in, I saw the team for myself. They were running around…they were just so kind and accommodating.” Some of Honigman’s close friends were also allowed to be with him after 6 p.m. that evening.

Friends, colleagues offered prayers

A small group of his friends had gathered below his room, outside the Hospital on Taché Avenue, to recite the Mi Sheberach, a Jewish prayer for healing. “Between the chaplain, and me being on the phone with my church, and his friends saying the prayers for the sick outside on the street, Arch had everything. They accommodated us so graciously,” she said.

Honigman was rushed from the ICU to the Hospital’s Cardiac Catheterization Lab after going into cardiac arrest for the second time. He went into cardiac arrest once more while he was there. It was more than his body could take.

The end came only five nights after he had come to St. Boniface Hospital. Eight hours after being put on a ventilator, Archibald Honigman was gone by 8:30 p.m. on September 23.

“I had never been with someone who had passed before. He was peaceful and looked like Arch. His close friends and I stayed with him, and I held his hand until it was time for the synagogue to pick him up. All the staff and the doctors there made it comfortable, and as good as it could be for me and his friends who were allowed inside.”

Even on his deathbed, Honigman was a mensch (Yiddish: an admirable or honourable person) who wanted to thank his caregivers. The day before he passed, he asked his wife if she could make up a batch of her special iced sugar cookies for the ICU staff. It was in character for Honigman, who was famous for the catered lunches and Morden’s chocolates he lavished often on employees, friends, and family he appreciated.

Biondi could not respond in time while her husband was alive, but she delivered as promised three weeks later. Almost 60 handmade and individually wrapped sugar cookies, iced with Thank You delicately written on each one, given with a thank-you card to all the staff of the ICU.

“The cookies were a little late,” she said. “But it was just as Arch had asked of me – his final gesture of gratitude.”

Be a lifeline for front line health-care workers at St. Boniface Hospital, like those who cared for Arch Honigman. Donate today.