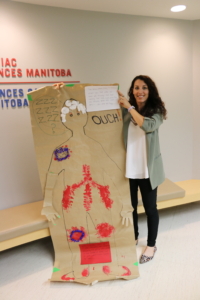

Clinical Nurse Specialist Emily Phillips is using arts and crafts to learn about patient experiences following open-heart surgery at St. B.

September 18, 2025

A researcher at St. Boniface Hospital has turned pipe cleaners, glitter, and colourful markers into instruments of medical research at St. Boniface Hospital.

A researcher at St. Boniface Hospital has turned pipe cleaners, glitter, and colourful markers into instruments of medical research at St. Boniface Hospital.

Emily Phillips, Clinical Nurse Specialist with the Cardiac Sciences program and PhD candidate in Applied Health Sciences at the University of Manitoba, has successfully created one of the first-ever definitions of what early mobility after cardiac surgery means, by having former patients share their experiences through art, in a process called body mapping.

Over three days in June of 2024, Phillips and her research team invited former patients who underwent various open-heart surgeries (bypass, valve surgery, etc.) to return to St. B a year to two years later. Gathered in the I. H. Asper Institute at the Hospital, Phillips asked two groups of participants “What was it like to first move after your heart surgery?”

She handed each person 6-foot rolls of poster paper, markers, glue, stickers, scissors, bubble wrap, and any other craft supplies they might need to make individual body maps.

“Art is a powerful way to put patients in the driver’s seat and really hear their stories how they want to share them,” explained Phillips. “It’s hard to put experiences into words, if I asked them to tell me about their experiences moving after surgery. I would get a very different story than what they’ve drawn on their body maps.”

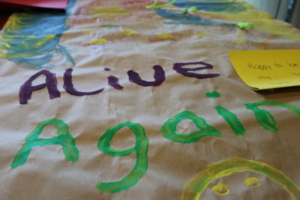

A body map is a life-size artistic representation of a person’s body, sort of like a self-portrait from a moment in time. The former patients were given the opportunity to express where in their body they experienced pain, what it felt like to first move, and what they were thinking about in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) following their surgery.

Definition of early mobility unclear

“It’s amazing, you can express so much more through art than you can through words. If I want to understand your thoughts, I’ll ask you with words, but if I really want to understand your experience, using art is a powerful way along with words. You can express so much more,” said Phillips.

“There wasn’t an agreed-upon definition of what early mobility is, in the ICU or after heart surgery,” she said.

“Based on how they described moving, we have created the first patient-informed definition of what early mobility after cardiac surgery is. We’ve created a definition that’s informed by patients and the ICU health-care team, and that’s the first time that I’ve seen that.”

Former patients expressed pain, confusion

“If we don’t understand the patient experience, then we’re not going to be able to do our best care for patients.”

The project was funded by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Participants had their bodies traced – some lying down, others while sitting. While they worked on telling their stories, they eventually started looking at each other’s body maps, asking questions and making suggestions. “It was amazing to see them working together,” said Phillips.

At the end of the day, they were asked to give their body maps a title, which included, Alive Again, Ouch!, Day of Confusion, and Moving?

Participants returned the following day for group discussions about their body maps. “So, it wasn’t us interpreting what they put on their body maps; they told us what these things meant,” remembered Phillips. “It was amazing seeing them enthralled and nodding, you could see them going through similar experiences and reliving them.”

Some depictions of pain were hard to misinterpret, such as the patient who drew red scissors stabbing into his back. Another participant glued rocks under his feet to show how unsteady he felt after his surgery.

“I didn’t expect the differences in how pain was experienced. I expected more of my leg hurt; my chest hurt. The back pain, the feeling of pressure on the shoulders – those parts surprised me, and we probably would have missed those if we had just been asking questions,” she said.

A few participants glued cotton balls around their heads; to show the confusion and fogginess they felt in the ICU. “Using cotton balls to show confusion was consistent for a lot of people. It was surprising to see how similarly they were describing their experiences there. I didn’t understand the extent of the confusion, the fear and the fog that sticks around, and how long it was there for.”

Next: sharing findings with care team

Next: sharing findings with care team

Before her planned graduation in the spring of 2026, Phillips will continue to share the findings of her research with the ICU health-care team at the Hospital.

“When we say early mobility, if we’re all thinking something different, we’re not speaking the same language. We’re not going to be able to work together as a team. If we don’t understand the patient experience, then we’re not going to be able to do our best care for patients,” she said.

“How do we explore and describe these experiences? How do we change how we deliver care, so that it better supports patients or better aligns with what they want? Meanwhile, staff are acting based on what they think is best for patients. How do we help them with more knowledge to do that well?”